"This is not democracy, because it came from spreading lies in darkness paid for by illegal cash from God knows where" – Carole Cadwalladr, lead journalist in the Cambridge Analytica exposé.

The results of the May 2022 Philippine elections sent shock waves across the world. Ferdinand Marcos Junior, son of the deposed dictator, and running mate Sara Duterte, daughter of the incumbent president, won the election count overwhelmingly with about 58 percent of the vote. In contrast, their nearest rivals received only around 28 percent in an election that drew a turnout of 80 percent.

The big question on many people’s minds is why and how the Marcos-Duterte team got the support of a majority of the voting public. Was it by freewill or contrived support? Or was it due to stealthy computer-encoded fraud? There is also that subsequent question of ‘what next’? For quite a few, how do you dissent when the majority are supportive of elected leaders who cannot be moral leaders? For those outside the Philippines, what should solidarity look like, now and for the next six years?

Former Vice-President Leni Robredo during a press conference in Naga City (© Yummie Dingding).

What just happened?

In this article, we offer one set of explanations that we do not argue to be correct but may be of use in sorting through the tangle. We think Marcos “won” because he captured the public sphere. With the deployment since 2015 of the tactics of online reputation laundering and political microtargeting that combines data-driven voter research with personalized political messaging, the election evolved into something else other than a fight between the ‘pink movement’ and the red-green Marcos-Duterte camp.

Rather, the elections turned into an asymmetric battle dominated by a well-funded machinery of mostly unseen non-traditional actors, but directed by the usual suspects, working since 2015 using new, tech-based and data-driven tools that systematically supplied wholesale disinformation, manipulated public opinion, and quietly perverted everyday narratives accessible to most Filipinos. The disinformation, narratives, and messages of political micro-targeting were eventually refined and sharpened over the six years of the Duterte administration to make the political coalition led by the top families (Marcos, Duterte, Macapagal-Arroyo, and Estrada) the preferred choice of voters.

An illiberal consolidation

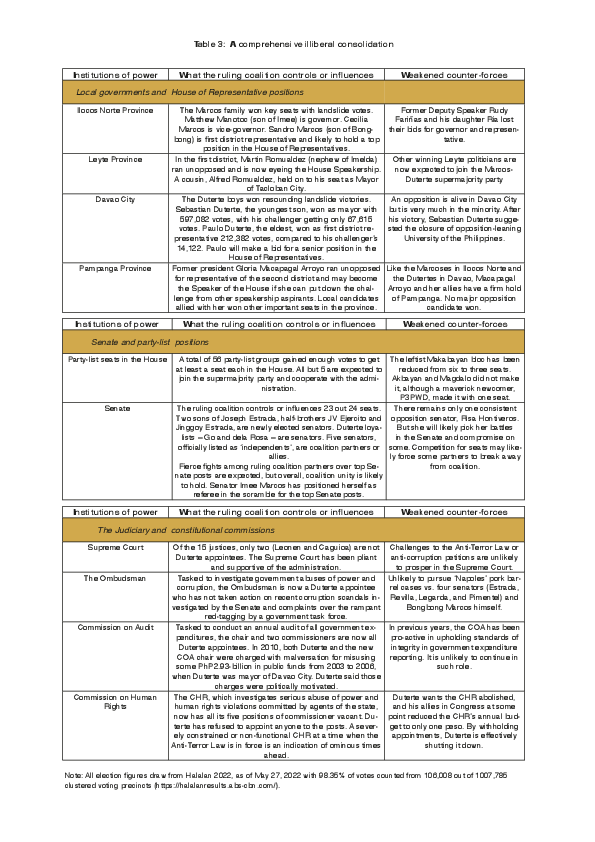

Power is now under the control of the red-green coalition on top of the political predatory chain. Uniting to protect their common interests, the Marcos, Duterte, Macapagal-Arroyo, and Estrada families, along with their allies, have secured the top prizes nationally and won by landslides in their respective home races. This power will soon consolidate with the creation in Congress of a supermajority ‘party’ that will be set up not only for a division of the spoils, but also to co-opt or debilitate what remains of an ‘opposition’. Not only is the institutional system of checks-and-balances effectively disabled. This coalition also rules with an Anti-Terror Law in place that gives them martial-law-like powers. The attached table 3 presents who has control of various institutions of power, and shows that the Philippines is now seemingly a one-party state (last update on June 30, 2022).

On top of the incapacitation of the system of checks-and-balances, the passage of the Anti-Terror Law in December 2021 bodes rough weather ahead. With this law, the various forces of the police and the military along with their intelligence agencies that have long track records of human rights abuses will not feel constrained by any accountability mechanism from either Congress, the Supreme Court, or the constitutional commissions. The country can expect red-tagging to be the standard practice in silencing people and organizations declared to be ‘enemies of the state’.

Local politicians, especially those elected to positions in the Bicol, Panay, and Negros provinces where Marcos and Sara Duterte did not win the vote, will be under great pressure to defect or compromise.

Activists in denial

Many progressive activists are in denial on the reasons about what happened. They seemingly could not process the reality that there actually may be a genuine constituency of ordinary Filipinos actively supporting illiberal regimes and illiberal policies. During the election campaign, there was a popular slogan that went “Ang bumoto ng magnanakaw, kasabwat. Ang bumoto ng tapat, kabalikat” (Whoever votes for the thief is an accomplice. Whoever votes for the honest one is a comrade). The Marcos-Duterte landslide shows most voters do not mind being accomplices. They appear to prefer messages of accommodation and convenience, like the ‘unity’ that Marcos offered as a solution to most of the country’s problems, over the more difficult goals of good governance and human rights.

The next section explores possible explanations on why a country that deposed a dictator a generation ago would now vote for the son who enjoys the benefits of plunder. What could be an explanation for the mass transition from the liberal achievements of the 1986 EDSA uprising to the illiberal election results of May 2022?

The public sphere according to Habermas

The public sphere is a concept introduced by German philosopher Jürgen Habermas in 1962. He defines it, first of all, as a realm of social life, accessible to all citizens, in which something approaching public opinion can be formed. A portion of that public sphere, he explained, comes into being in every conversation in which private individuals assemble. Whenever citizens confer with each other in an unrestricted fashion, these conversations form a ‘public body’.

Many different public bodies come and go to constitute the public sphere. Thus, social spaces where private individuals gather – such as cafés, town halls, or family gatherings – to discuss issues of general interest are, in this sense, the parts that form the public sphere. Places where ordinary Filipinos interact informally – malls, tambayans (waiting sheds), plazas, sari-sari stores (small kiosks), marketplaces, or even by the office water cooler – to exchange common knowledge (sometimes called tsismis) are part of the public sphere.

Non-governmental opinion making

Habermas made a further qualification – that a public sphere is political when the open discussion deals with objects or topics connected to the activity of the state. He clarifies that state authority, though seemingly an executor of such a political public sphere, is not a part of it. In other words, the state and the public sphere do not overlap. The public sphere is where non-governmental opinion making takes place. It follows therefore that political actors across the spectrum, including state authorities, will try to control various means of communication – radio stations, TV shows, newspapers – to transmit information and influence the opinions being formed in the public sphere. The rationale is simple – influence over the public sphere means gaining or preserving the control of power.

Election camapign event of Presidential candidate Ferdinand 'Bongbong' Marcos Jr. in Tondo, Manila. Supporters hold an image of the candidate's father, dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. who ruled the country from 1965-1986 (© Yummie Dingding).

Facebook replaces Plaza Miranda

Thus, Habermas investigated cases in history that showed how big companies and government institutions started influencing the public sphere, oftentimes invisibly, thus turning private individuals into primarily consumers and receivers, rather than citizens exercising agency. The public spheres he examined mutated from spaces of rational discussion and debate into realms of mass cultural consumption and administration by dominant elites. A key target of his critiques was the mainstream media – newspapers and broadcast networks that were state-controlled or owned by big firms and business moguls promoting their interests and particular political agenda. Habermas called this ‘the structural transformation of the public sphere’.

Before martial law, the phrase ‘Ipagtanggol mo sa Plaza Miranda!’ (Defend it in Plaza Miranda!) was often heard. It meant that anyone who wants to a make a political claim or statement should bring it out into that busy open square in front of Quiapo Church in Manila and defend it before the gathered public. Plaza Miranda – where politicians, preachers, and the public converged and debated freely – became a symbol of a political public sphere.

Today, 60 years after it was coined, the ‘public sphere’ along with the public bodies that comprise it have radically changed in ways that Habermas may have never ever anticipated. At the risk of oversimplification, it may be said that Plaza Miranda has been replaced by Facebook, TikTok, YouTube, Twitter, Instagram and many other social media apps. Much of the public sphere has gone digital.

Why are we where we are?

In today’s digital age, new incarnations of the structural transformation of the public sphere emerged all over the world, and the Philippines provides a model case study. Over the last decade, business and market surveys conducted by global advertising watchdogs show that the Philippines is among the top three countries in the world with the highest per capita internet usage and social media engagement.

Datareportal, published by market research companies We Are Social and Hootsuite, showed that there were 76.01 million internet users in the Philippines in January 2022, which is 68 percent of its total population of 111 million (of which 48 percent lived in urban centres, while 52 percent lived in rural areas). The Philippines has 66 million registered voters, of which some two million are overseas.

While this digital population of 68 percent is low compared to northern Europe which has a 98 percent internet penetration rate, what makes Filipin@ internet users different is the extraordinarily high amount of time they spend on the internet and using social media. The German market and consumer data firm Statista reports that Filipin@ internet users spent an average of 10:27 hours accessing the internet on various devices each day during the third quarter of 2021, compared to the global average of 6:58 hours.

More importantly, Filipin@s spent 4:06 hours using social media each day, the highest in the world. In comparison, the global average is 2:27 hours. To Filipin@s, especially to families who have members dispersed in diasporas all over the world, social media has become not only the means to stay in touch, but also to socialise, read the news, get tsismis, look for work, flirt, study, get advice, and so on. As such, Statista cites how the Philippines has been called the ‘social media capital’ of the world. In addition, Filipin@s are known as early technology adopters and highly internet savvy. In fact, it is the infrastructure that cannot keep with the demand, especially for an archipelago with over 23 major islands and 7000 other smaller ones.

No bank account? No problem, Filipin@s have their phones

The company, GMSA Intelligence, reports there were 156.5 million cellular mobile connections in the Philippines at the start of 2022. The high figure, which is way above the total population, is not unusual because most people around the world make use of more than one mobile connection, for example, one for personal use and one for work. Workers in the trolling industry are also known to use dozens of mobile connections as their tools of the trade.

The density of cellular mobile connections in the Philippines appears as the key reason why Filipinos’ financial habits have radically transformed. The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas or the Central Bank reports that in 2019, only 29 percent of Filipin@ adults have bank accounts. The global average in comparison, according to the World Bank, is 55 percent. Neighbouring countries have also much higher levels:

Thailand – 82 percent; Taiwan – 94 percent; Malaysia – 85 percent; Indonesia – 49 percent (also an archipelago like the Philippines); and India – 80 percent. The United Kingdom has 96 percent, and the United States has 94 percent. Yet despite the low level of bank account holding in the country, the transmission of money within and across borders is not a problem. Though most Filipinos neither have bank accounts, insurance, nor credit cards, they have their mobile phones. They transfer money, pay bills, make purchases, pay debts, or borrow money using their mobile phones. The diaspora’s padala system of sending money back home has become digitized with the use of mobile phones.

Digitalized Wallets

There are now over two dozen money transfer apps in the Philippines and online vendors and retailers like Lazada and Shopee that make it difficult even for global giants like Amazon to penetrate the country. Gcash, the leading Filipino money transfer company, says its app turns one’s mobile device into a digitalized wallet, thus creating ‘positive and transformative disruption’ in the financial services sector. Gcash confirms the BSP report that 71 percent of Filipin@s do not have bank accounts and adds that 26 percent, or one out of every four, do not have physical access to banks because they live in remote places or islands that would take a day’s travel to reach a bank branch. Less than 2 percent have access to credit cards, and only 23 percent of Filipin@s have insurance. Gcash reports in a personal interview on March 14, 2022, that up to 76 percent of Filipin@ adults use their app, while other similar apps cover the rest.

In other words, there is a very different type of public sphere – one that is embedded in everyday social media exchanges and mobile phone transactions – that has emerged in the Philippines. The creation of countless public bodies – online chat groups, family gatherings, or private broadcasts – can now be easily made online with notifications and updates automated. The Philippines is a classic case in the structural transformation of the public sphere in the digital age and this transformation is what has made reputation laundering and political microtargeting so much easier.

Vice-Presidential candidate Sara Duterte hugs a supporter on stage during an election campaign event in Balayan City, Batangas (© Yummie Dingding).

Reputation laundering and political microtargeting – how it’s done

In August 2010, The Guardian published what became a series of reports over the years on ‘reputation laundering’ and how London had become its centre. London’s PR firms were earning millions of pounds promoting regimes with some of the world’s worst human rights records, like Saudi Arabia, Rwanda, Kazakhstan, and Sri Lanka. Politicians from Russia, Madagascar, China, and Sudan also sought British PR firms to burnish their image.

The deep involvement of PR firms in reputation laundering and the harm they cause are shown in the case of Bell Pottinger, one of the leading PR agencies. In September 2017, Bell Pottinger was expelled from the industry trade association (the Public Relations and Communications Association) after an investigation found that it was behind a secret campaign to stir up racial tensions in South Africa. Bell Pottinger was hired by the holding company of the Gupta family, a wealthy Indian-born family with extensive business interests in South Africa, to raise racial anger against “white monopoly capital” and “economic apartheid”, so that attention may be drawn away from what many regarded as corrupt relationships that the family enjoyed with then South African president Jacob Zuma.

From traditional to digital tools

A lot of the mischief done to stir those racial tensions appears to have been done online. Like the Philippines, South Africa is also one of the top three countries in the world with the highest per capita usage of the internet and social media. It became evident that the tools PR firms used have moved from the traditional, like placing ads in newspapers, radio or television, to the digital, like spreading disinformation on social media.

According to Chris Wylie – the whistle blower who blew the lid on Cambridge Analytica’s data-fueled microtargeting using hijacked personal data on Facebook –, social media created a new environment where campaigns could now appear as if your friend was just sending you a message, without realizing the actual source or how that message was created with calculated intent.

Personal profiles and digital footprints for sale

At the heart of this new environment is a new commodity – the personal profiles and digital footprint that people leave every time they open apps like Facebook. Those profiles and digital footprint are valuable for advertisers, election campaigners, and reputation launderers. Wylie claimed that in 2019, Facebook on average made US$ 30 from each of its 170 million American users. As such, though we think of Facebook as a free service, in reality “we pay with our data into a business model of extracting human attention.”

Facebook, continues Wylie, was designed with patterns that encourage users to share more and more about themselves, from the commercial (where we shop, what we buy, what we fancy) to the political (who we follow and who we despise). Trawling through our digital footprints in this way would land a traditional postal worker in prison. Live geo-tracking, once reserved for convicts’ ankle bracelets, was added to our phones. Wylie points out that what would have been wiretapping in years past became a standard feature of countless applications.

Private surveillance networks

It became easy for Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and other apps, continues Wylie, to create “communities” that were in reality private surveillance networks where experiments can be conducted to test how people behaved or changed their opinions. It also provided data that is so cheaply acquired on how voters can become targets for confusion, manipulation, or deception, and how truth can be replaced by alternative narratives and virtual realities.

Wylie and his colleagues – a few of them academics from reputable universities – created models and algorithms that devoured huge volumes of information on one end, drawn from the personal profiles harvested on social media, or the data points – the ‘likes’ a user makes on products, news items, or comments. The computer model then identified and isolated issues, - divided the electorate into very narrow segments, and proceeded to predict which individuals are best targets for different types of persuasion. Different models are tested and retested, until desired changes in opinion show which are more effective (see Table 2).

The principle is not difficult to understand

Election campaign strategists, for example, have always used demographics – gender, age group, educational attainment, income status, and so on – to inform their decisions on messages to use, areas to focus on, or when to attack or remain silent. Digital footprints on social media are perhaps a thousand times more valuable than such demographic data. Microtargeting is about communicating selected messages to selected voters. When digital footprints are cross-referenced with other information that could be obtained elsewhere – like a voter’s mortgage, magazine subscriptions, car model, holiday destinations, and so on – an unseen machinery that creates ‘scores’ on people is built to provide the critical horsepower of a modern election campaign.

Reputation laundering is like money laundering – the process of turning what is dirty into something clean or acceptable. It creates harm, like racial tensions in South Africa, or the rehabilitation and normalization of the Marcoses. The principal difference is that while money laundering is a criminal offense, reputation laundering isn’t. The problem, explains Wylie, is that because the possible crimes of reputation laundering happen online and not in a physical location, the police and regulators could not agree on who has jurisdiction. Because what has been done involved apps, software, and algorithms, people throw up their hands in confusion trying to understand what they were investigating.

The project to rehabilitate the Marcos Family

It was sometime in 2015 when the now defunct political consultancy firm Cambridge Analytica received a request “straight from Bongbong Marcos” to rebrand the Marcos family’s image on social media. This was according to Brittany Kaiser in a July 2020 interview with Rappler’s Maria Ressa. Kaiser worked from February 2015 to January 2018 as Director for Business Development at SCL Group (formerly Strategic Communication Laboratories), a British behavioral research and strategic communications company and military contractor that was Cambridge Analytica’s parent company.

The request from Marcos, said Kaiser, was taken up and debated internally by the staff. Some didn’t want to touch it, but the CEO, Alexander Nix, “saw it as a financial opportunity.” In the last quarter of 2015, Nix visited the Philippines “where he met with many candidates and solidified a partnership with a top political consultancy.”

Cambridge Analytica and the collection of Facebook profiles

However, in March 2018, a global scandal erupted when Chris Wylie, by then Cambridge Analytica’s Director of Research, was overcome with guilt about their unethical and possibly criminal practices. He released a cache of documents to UK newspaper The Guardian showing how the firm collected up to 87 million Facebook profiles in the US and the UK without the consent of users, and which were subsequently used predominantly for political microtargeting apparently to influence the UK’s June 2016 Brexit vote and the US November 2016 presidential elections that Donald Trump won.

Facebook was later fined USD 5-billion in the US and GBP 500K in the UK for exposing its users to a ‘serious risk of harm’. On May 18, 2018, Cambridge Analytica filed for bankruptcy.

Presidential candidate Ferdinand 'Bongbong' Marcos Jr. during a rally in Bacolod City, Negros Island (© Yummie Dingding).

Rebranding the family name

Kaiser explained that Cambridge Analytica was an expert in microtargeting, or “the practice of manipulating an individual’s thoughts and sentiments through disinformation tactics with the use of personal data.” She said that the Marcos’ effort to rebrand the family was “historical revisionism, done in a data-driven and scientific way.” You undertake just enough research, she explained, “to figure out what people believe about a certain family, individual, or politician, and then you figure out what could convince them to feel otherwise.” The company would keep on running tests – for example, releasing different versions of attacks and disinformation against Leni Robredo while praising Bongbong Marcos" – until you actually start to see changes in people’s opinions and attitudes.”

In testimonies given before subsequent investigations, it was revealed that the personal data of users, collected through Facebook’s Open Graph platform, was run through an app called “This is Your Digital Life” which built psychological profiles of individual users, that can then be used to inform on a user’s individual preferences, including what may be tried to change that user’s opinion of a politician. Some may be convinced by urban legends or conspiracy theories; others by ad hominem attacks against opponents or manufactured scandals; others by groupthink emerging from an inundation of comments and interaction about a post; and so on.

Reputation laundering and microtargeting at work

Despite the Marcos family’s denial of Kaiser’s claims (that included veiled threats of legal action against those making it or repeating those claims in the media), subsequent research revealed the extent of the historical revisionism and deployment of political microtargeting by the Marcos-Duterte coalition in the Philippines. Bongbong Marcos lost the 2016 vice-presidential elections to Leni Robredo, perhaps because there just wasn’t enough time for the microtargeting to work. But Duterte, who openly partnered with Marcos in the last few weeks of the 2016 elections (and dropped his official vice-presidential candidate, Alan Cayetano), won the elections.

The first research published, by Cabañes and Cornelio in 2017, tracked Duterte’s rise to power to how trolls with both verified and suspicious accounts weaponized various social media platforms to attack Duterte’s critics online at every opportunity, thus creating a competitive advantage through the ‘curse of hate’ in the everyday narratives emanating from those platforms. Laptop screens and smartphones in the Philippines, said a 2018 research by Ong and Cabañes, were used to manipulate public debate, hijack mainstream media agenda, and influence political outcomes by the ‘architects of networked disinformation’, which they defined as “the professionalised and hierarchized group of political operators who design disinformation campaigns, mobilize click armies, and execute innovative digital ‘black ops’ and ‘signal scrambling’ techniques for any interested political client.”

The Marcos' rehabilitation under Duterte

During the six years of the Duterte administration, the project to rehabilitate the Marcos image continued. By October 2021, the ‘Digital Public Pulse’ conducted by the Philippine Media Monitoring Laboratory of the University of the Philippines Diliman reported that the Marcos project had succeeded, but very few took notice. Thus, even before the campaign for the 2022 elections started, Bongbong Marcos was already the leading candidate enjoying a massive margin. The research showed that:

- The political groundwork for the 2022 Philippine elections has been operating since 2016 and has by the start of the campaign period already matured to run massive but insidious campaigns, with ‘below-the-radar’ anti-democratic actors hijacking the political discourse on social media.

- Marcos rose in influence and expanded reach across audiences through the algorithmic cultivation of YouTube communities, i.e., the rise of hyper-partisan political channels that guised their content as ‘news’, launched ‘attack’ campaigns, and distorted political popularity. It was through YouTube that urban legends – e.g. about the Marcos family’s wealth and the martial law period as a ‘golden age’ – were cultivated. Because these urban legends were not negative or ‘attack’ posts and did not use inflammatory language, it did not technically violate YouTube’s community guidelines, thus the lies and disinformation were allowed to thrive.

- Twitter was an ‘interaction network’ where obscure accounts were most influential in being popular and noisy while news media became only secondary in influence. The interaction network of Marcos on Twitter grew significantly from having no distinct interaction cluster in the first quarter to having his own distinct community in the second quarter, overtaking Robredo’s.

- On Facebook which is essentially a ‘sharing network’, Robredo-related groups circulated more content and information, but it was the Marcos- and Duterte-related accounts that expanded in reach and engaged more diverse communities.

A supporter of Presidential candidate Ferdinand 'Bongbong' Marcos is waiting to shake hands with his candidate in Damariñas, Cavite (© Yummie Dingding).

“A lie told a thousand times becomes the truth”

Findings of Tsek.ph, a fact-checking collaboration of 34 agencies using Facebook’s Crowdtangle software, further corroborate the findings. One claim Tsek.ph examined was a post that “no critics of Marcos were arrested during martial law.” Although obviously false and a historical distortion, it was viewed an astounding 187 million times. The huge number may be due to troll armies outside the country sharing and circulating the post, which means that the false claim may have been drilled down to 66 million Filipinos voters repeatedly. Bundled together with other similar claims and fake news and projected actively across social media platforms, it is not difficult to imagine what the typical Filipino voter, who spend an average of four hours a day on Facebook and other social media, absorbed.

The Marcos-Duterte campaign relied on a massive political infrastructure on social media, aided by marketing advisers and political operators working behind the scenes, using the tools of micro-targeting and running tests until people’s opinions and attitudes change in the public sphere – in favor of a rebranded Marcos family. And this is only the tip of the iceberg. More work needs to be done to monitor and measure the penetration and tracking, and the associated operations that continue to be deployed even after the elections to ensure that Filipino digital users remain on side in the continuing debates and discussions in the public sphere.

Quite intrusion and its affect on the political reality

To conclude, the systematic and quiet intrusion into the Filipinos’ public sphere has a huge influence on their political reality. As suggested by Assistant Professor Fatima Gaw, head researcher of the Digital Public Pulse project, disinformation leads to biased perceptions, which in turn leads to receptiveness to political manipulation. The Marcos family brand has been successfully rehabilitated by exposing and engaging Filipinos with disinformation, troll comments, and historical revisions – up to four hours each day.

Social media apps as doorways into the minds of voters

Marcos was bold enough to make that challenge, because as explained by Fatima Gaw, he had already “built an alternative information ecosystem that supports, affirms, and legitimizes the political ‘reality’ that fits his campaign messages. Marcos and his handlers had, by then, built a massive infrastructure and stockpile of ‘news’ websites, YouTube ‘educational’ content and urban legends, Tiktok trivia videos, and thousands of commenters and click armies that corroborate the narratives of rebranding.

What the brazen Marcos challenge reflects is that Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and the other apps were no longer just companies that turned digital footprints of its users into data for sale to whoever would want and pay for it: social media apps have become doorways into the minds of voters. There is a need to accept that what has been done could simply not be undone quickly. Unfortunately, there are no quick fixes for successfully laundered reputations and manipulated public opinion. The Philippines is in a quagmire from which there is no easy way out.

Men with t-shirts of Senate candidate Mark Villar of the Hugbong Pagbabago Party smear a wall with paintings campaigning for Presidential candidate Leni Robredo and Vice-Presidential candidate Kiko Pangilinan in Las Pinas (© Yummie Dingding).

What can be done?

Fatima Gaw explains that existing interventions do not work in the short run. Although Facebook, Twitter and YouTube have now taken down accounts exhibiting ‘inauthentic behaviour’ and violating ‘community standards’, these actions are too late and too slow to make any difference at all. It is like firefighters dousing the flames after the house has already been destroyed.

Fact-checking, she says, may provide new materials for circulation, but will only appeal to particular kinds of audiences who are in the very small minority. It will not have the same virality to quickly reverse the urban legends on the elder Marcos’s war time exploits, his capture of the Yamashita treasure, or claims that the cases against the family are false because until now none of them had been jailed.

Most importantly, states Gaw, the regulation of political microtargeting is useless because there is no way to police seemingly ‘organic’ content on social media. The solution prescribed by many is to crack down hard on online disinformation and misinformation through regulation and censorship. But others believe such a response may also pose social and political risks – for example, it may become a license to curtail freedom of expression and undermine other human rights.

After his election in 2016, Rodrigo Duterte radically increased his communication and propaganda expenditures to unprecedented levels at the expense of funding allocations to the defense, social welfare, and education budgets. The reason has now become clear. Despite Duterte’s failed “war on drugs” and the thousands killed, his capitulation to Chinese interests in the West Philippine Sea, and the protection he provided to cronies who made money from the public contracts during the pandemic, he will step down from power with the highest acceptance and popularity ratings ever – fueled no doubt by the continued operations of reputation laundering and political microtargeting.

So what else can be done? Below are some ideas.

Reclaiming social media

Many Filipino netizens, frustrated and disillusioned by the Marcos victory, deactivated their social media accounts after the elections. Some did it to protect their mental health, others did it to avoid susceptibility to manipulation and microtargeting.

While those decisions are understandable, it may be asked: can forms of ‘political judo’ be possible on Facebook and the other apps, so that social media may be reclaimed, if only to level the playing field? In other words, instead of deactivating, could disillusioned netizens continue with social media engagement in ways that turn the opponents’ attacks against them, like judo? Another way of putting it is to use the very same tactics of reputation launderers against themselves. If Facebook, TikTok, YouTube or Twitter are the ‘crime scene’ where reputation laundering and political microtargeting took place, couldn’t those tactics be countered too on these very same platforms?

One example of political judo is how women activists in the US respond to sexist and misogynist comments thrown their way. As the New York Times put it, the women activists did not just get mad, they cashed in. When women activists were called ‘Abortion Barbie’, addressed with ‘Fetch!’ as if they were pets, or told about ‘legitimate rape’, they turned the outrage over those sexist remarks into a political fundraising tool, so that they could continue with their advocacy.

“A world without facts means a world without truth and trust"

The successful laundering of the Marcos image could be turned into the impetus for regrouping and raising resources to re-establish the truth online. As Maria Ressa emphasized, “a world without facts means a world without truth and trust.” Now that an alternative (dis)information ecosystem is in place, a mobilization towards re-establishing the truth should be sustained.

The ‘pink movement’ created lots of chat and community groups on social media that became ‘nerve centres’ during the campaign for exchanging information and troubleshooting – for example, how to engage with relatives on the other side. These should not be disbanded and kept as venues for brainstorming and innovation.

Reclaiming social media, however, is easier said than done. Many users need protection safety online from troll attacks and violations of their privacy. But it is also important to remember Wylie’s advice: “If we choose to wait for regulators, investigators, or prosecutors to undo what has been done, nobody will come.”

Political interlopers needed to build resilience to disinformation

An important point raised by Fatima Gaw is that “the boundaries between social spaces online are more porous than you think,” which means those same spaces where disinformation and manipulation prospered can still be ‘infiltrated’ or nudged in certain ways by political interlopers. Filter bubbles and echo chambers, Gaw said, are not empirically proven. Hence, ‘affordances’ – or what people notice or experience to change their views – can be brought into digital and media spaces. Diverse perspectives and information that disprove laundered reputations are still possible in that alternative information ecosystem of fake news and disinformation.

For example, one of the most important tweets during the campaign was that posted by Manny Pacquiao. The famed boxer was ridiculed as stupid or ‘weak in the head’, so he responded by tweeting “ang totoong bobo ay yung boboto sa magnanakaw” (the really stupid ones are those who vote for the thief). That post by Pacquiao, who has 18.8 million followers on Facebook and 2.6 million on Twitter, will have lingering effects in the public sphere.

Presidential candidate Leni Robredo and Vice-Presidential candidate Kiko Pangilinan during a rally at the Quezon City Memorial Circle (© Yummie Dingding).

Endorsements that create legitimacy

It is also in this regard that the open endorsements of pink candidates by celebrities, universities, church leaders, and many others have long-term value that should be nurtured and sustained. The ‘Darna’ celebrities for example – massively popular film stars and singers who played the role of Filipino folk superheroine Darna (similar to America’s Wonder Woman) and who went all out to support the Robredo-Pangilinan team – have between them over 50 million followers on Facebook alone. Their endorsements are etched in the popular consciousness, leading many pundits to comment that had the election campaign stretched by a few more weeks, the Marcos lead would have been significantly whittled down that his victory would have not been ensured. Those endorsements create legitimacy and can make Marcos-Duterte microtargeting less effective.

Sustaining this legitimacy and building the resilience to disinformation require deliberate and conscious action from users to be political interlopers who will continue their engagements in the public spheres.

Applying the techniques of anti-money laundering

Another approach that may be considered is to apply anti-money laundering measures to reputation laundering.

Until around 2005, money laundering is only a ‘predicate offence’ in most jurisdictions – which means it is a crime only when linked to a more serious primary offence, such as drug trafficking, robbery, or plunder. On its own and without those links, money laundering is regarded simply as unethical practice. However, since the enforcement of the UN Convention Against Corruption in 2006, money-laundering became a stand-alone criminal offence.

Following recent experiences in different countries, reputation laundering should also now be turned into at least a predicate offence, and at most a standalone criminal act. If it is linked to cleaning the reputations of those who have had criminal convictions, reputation launderers should be accordingly charged. The point is to remove any argument or doubt that what’s being done is not just unethical but criminal.

'Due diligence'

To avoid being charged with money laundering offences, banks are compelled to conduct ‘due diligence’ or know-your-customer (KYC) rules. Banks must know the real identity of the customers who open accounts with them. And registers of the real and ‘beneficial owners’ of those accounts should be made publicly accessible. This means, for example, that a customer who has different business interests or properties can have multiple bank accounts but can only have one single truthful identity and address known to the bank. Something similar could easily be developed for the various social media platforms and make it easier to identify troll accounts. Trolls can behave as they wish on social media – because that is actually covered by the freedom of speech, unless it involves death threats or something similar. But their identities and addresses will always be known to the social media company and can be supplied to investigators whenever necessary.

Anti-money laundering rules also compel banks to submit Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs). As Carole Cadwalladr mentioned in her speech following the Brexit referendum and US 2016 elections, Facebook and the other platforms have become a crime scene, and that the gods of Silicon Valley have the evidence. There should be a way that such evidence can be disclosed to relevant authorities, or in their absence, to media organizations with accountability.

A Fact-Finding Commission

A final suggestion is the creation of a Fact-Finding Commission on the Future of Democracy in the Philippines and Similarly Situated Countries. This Commission will carefully and systematically uncover and document especially the acts purposely hidden from view, so that they may be fully understood and appropriate short- and long-term counteractions may be developed and taken. The capture of key parts of the public sphere in the Philippines is not a simple domestic issue – it is a manifestation of a global problem on how reputation laundering and political microtargeting have become largely unseen instruments for the manipulation of public opinion and the subversion of democracies. At the very least, it ushers in a new political environment with new actors and new tools that need to be fully understood. If not properly examined, documented, and analyzed – the tools and tactics deployed, particularly the spreading of the curse of hate to gain competitive advantage over political opponents, are bound to repeat in other parts of the world.

German and European NGOs interested in the future of democracy, tackling the impact of new technology, and supporting development and democratization in the Philippines should consider coming together and lead in setting up such a commission.

Supporters during a Uniteam rally in General Trias, Cavite (© Yummie Dingding).

A closer view at the May 2022 elections

Two curious outcomes from the May 2022 Philippine elections needs closer inspection. First, the May 2022 results is the first time in recent Philippine election history that the winning presidential candidate got significantly more votes than the top senatorial candidates. To illustrate:

- In 1992, Fidel Ramos won with 5.32 million votes, which is less than the votes received by all winning 12 senators. On top was Tito Sotto with 11.79 million; the twelfth was Freddie Webb with 5.93 million.

- In 1998, Joseph Estrada won with 10.722 million votes, less than top senatorial candidate Loren Legarda’s vote of 14.93 million.

- In 2004, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo won with 12.95 million votes, less than top senatorial candidate Mar Roxas’s vote of 19.37 million.

- In 2010, Benigno Aquino III won with 15.2 million votes, less than top senatorial candidate Bong Revilla’s vote of with 19.51 million.

- In 2016, Rodrigo Duterte won with 16.6 million votes, less than top senatorial candidate Franklin Drilon’s vote of 18.6 million. Fifth placer Dick Gordon had 16.7 million votes.

- However, in 2022, Ferdinand Marcos Jr got over 31 million votes, which is more than top senatorial candidate Robin Padilla’s vote of 26 million.

The second curious outcome is that the May 2022 Philippine elections produced sore winners and triumphant losers. The Marcos-Duterte camp won by a resounding landslide as far as the results go, yet no street parties were held, no motorcades with confetti were seen, no thanksgiving festivities launched, and no massive congratulatory messages exchanged. The diplomatic community was also muted. It took three days before the first congratulatory message – from China – was heard, and over four days before other countries started trickling in with carefully worded messages. At the same time, the Marcos trolls did not pause with their unrelenting attacks. They continued their online bashing, and in particular attacked and defiled the announcement of Leni Robredo that with the elections finished, work starts anew in organizing an Angat Buhay (Life Uplifting) NGO for economic rehabilitation and livelihood support. Trolls called the announcement an insurgency, and the beginnings of a shadow government.

Conclusion

It needs to be made definite and unambivalent that the May 2022 Philippine elections is not democracy. Rather, it was the capture of the public sphere – funded most probably by stolen money, using data-driven techniques that were most likely unethical and involved violations of privacy, that unrelentingly attacked and tried to destroy that reputation of the main opposition candidate for over six years, and which mobilized thousands of trolls and click armies inside and outside the country. There never was a level playing field. It was a subversion of democracy.

Brittany Kaiser said in the documentary ‘The Great Hack’ that the British government considered Cambridge Analytica’s methodologies and microtargeting tools to be ‘export-controlled’, meaning those tools were considered a weapon – more specifically, weapons-grade communication tactics. She said that the sole worth of Google and Facebook is that they own, possess, and have commodified the personal data of people around the world. The best way to move forward, she stressed, “is for people to really possess their data like their property.”

A long-term push back to reclaim the public sphere is necessary. With state capture nearly complete, the pink movement of bayanihan and community pantries needs to stay its course, with a readiness to revive the ‘parliament of the streets’ and the tactics of non-violent civil disobedience if necessary.